WHEN JUSTICE COMMITS CRIME: PART 3

BAIL, RISK, AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF “BAIL JAIL”

Across the United States, bail reform has followed two sharply different paths.

In some jurisdictions, reform has been guided by the constitutional presumption of innocence. Money has been removed from the pretrial equation, and release is based primarily on the expectation that a defendant will appear for court. Conditions are limited, detention is narrowly defined, and liberty is treated as the default.

In others, including Indiana, bail reform has taken a different form. Cash and surety bonds remain central, but are now layered with risk assessments, pretrial supervision, and community corrections. Release is no longer simply a matter of posting bond. It is conditional, supervised, and monetized.

This structure produces what can fairly be described as “bail jail”: a system in which individuals pay for release, yet remain confined—physically, financially, or both—before guilt is ever adjudicated.

Trust-Based Reform Elsewhere

States that have eliminated or sharply limited cash bail operate on a simple principle: if the purpose of bail is to ensure court appearance, then wealth should not determine liberty.

Under these systems:

- Money is not required for release.

- Detention is reserved for narrowly defined circumstances.

- Compliance is measured by appearance, not payment.

- Pretrial conditions are minimized.

The constitutional logic is straightforward. The Eighth Amendment prohibits excessive bail, and due process requires that pretrial restraint be justified by necessity, not convenience (Stack v. Boyle, 342 U.S. 1 (1951)).

Indiana has not adopted this model.

Indiana’s Bail Structure: Money First, Liberty Later

Indiana law continues to authorize cash and surety bonds as primary mechanisms of pretrial release (see Ind. Code § 35-33-8-3). In theory, posting bond secures liberty. In practice, bond often serves as an entry point into a second system of control.

Defendants who post bond may still:

- remain incarcerated while awaiting placement in pretrial programs,

- be ordered into community corrections or house arrest,

- incur daily supervision fees,

- face revocation based on perceived noncompliance.

The result is not release, but conversion—from jail custody to supervised confinement.

IRAS-PAT: Risk Assessment as Financial Extraction

Indiana mandates the use of a risk assessment tool in many pretrial contexts: the Indiana Risk Assessment System – Pretrial Assessment Tool (IRAS-PAT) (see Ind. Code § 35-33-8-3.8 and Ind. Criminal Rule 2.6).

IRAS-PAT is presented as a neutral instrument designed to assist courts in determining appropriate pretrial conditions. In practice, it functions as a gatekeeper—not only of liberty, but of financial capacity.

While the tool is nominally advisory, its outcomes frequently justify:

- continued detention,

- placement in pretrial supervision,

- assignment to community corrections,

- or imposition of restrictive conditions.

Each of these outcomes carries cost.

Pretrial Detention and the Erosion of the Defense Fund

Pretrial detention has an immediate and predictable consequence: it drains the defendant’s financial resources before trial even begins.

When a defendant is jailed or placed under supervision:

- employment is interrupted or lost,

- income ceases,

- savings are diverted to bond, fees, and daily survival.

This has a direct effect on the Sixth Amendment right to counsel.

Although the Constitution guarantees the right to counsel, it also protects a defendant’s choice of counsel, within practical limits (United States v. Gonzalez-Lopez, 548 U.S. 140 (2006)). That choice becomes illusory when pretrial detention and supervision costs exhaust the very funds that would otherwise be used to retain private representation.

IRAS-PAT-driven detention and supervision do not merely manage risk. They reallocate resources—away from defense preparation and toward compliance with the state’s pretrial apparatus.

The effect is structural, not incidental.

Ashlynn Perigo: Bond Paid, Detention Continued

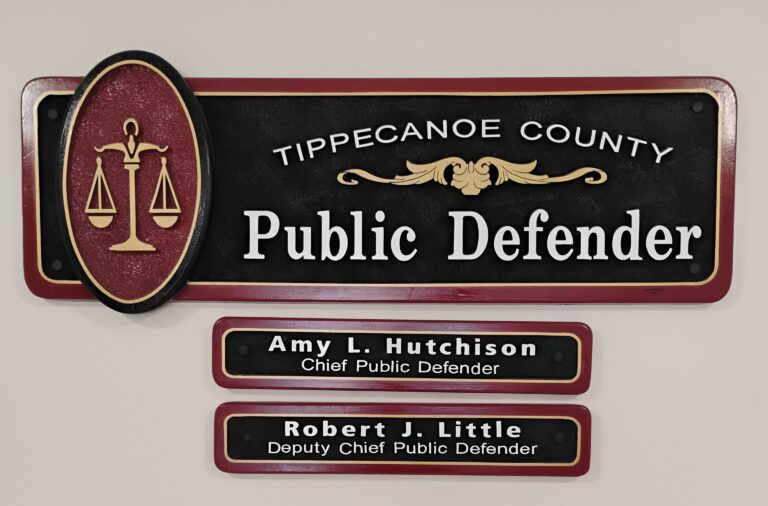

Ashlynn Perigo posted approximately $5,000 in surety and $500 in cash, satisfying the bond conditions imposed by the court. Despite this, she remained incarcerated in the Tippecanoe County Jail for weeks, not due to a new charge or violation, but because no bed was immediately available at Tippecanoe County Community Corrections (TCCC).

During this period:

- bond had been paid,

- release had been authorized in principle,

- detention continued solely due to administrative capacity.

Courts have long recognized that bail is intended to secure release, not prolong incarceration (Stack v. Boyle). Detention after bond has been satisfied raises serious constitutional concerns under both the Eighth Amendment and due process principles.

Whether such detention ultimately constitutes excessive bail is a legal determination. What is undeniable is the practical effect: payment did not restore liberty, and pretrial confinement persisted independent of risk or conduct.

Bobby Ray Rufus McDonald: Perception, Revocation, and Cost

Bobby Ray Rufus McDonald’s experience illustrates a different mechanism within the same framework.

His bond was revoked based on a judicial perception that he “looked high,” rather than a failed drug screen or documented violation. He was subsequently placed on house arrest through TCCC.

That placement required:

- a $150 sign-on fee, and

- daily supervision fees, paid while Mr. McDonald was living on disability income.

House arrest imposed continuous restrictions, enforced by the threat of reincarceration. The financial burden proved destabilizing. At one point, his electric service was shut off, a foreseeable consequence of layering supervision costs onto a fixed, limited income.

Here, IRAS-PAT-informed supervision did not mitigate risk. It magnified vulnerability.

From Bail to “Bail Jail”

These cases illustrate how Indiana’s pretrial system operates in practice.

- Bond can be paid without release.

- Bond can be revoked without objective violation.

- Supervision can replace detention while reproducing its effects.

- Risk assessment can justify both confinement and financial extraction.

This is bail jail.

Liberty becomes conditional not on guilt, but on the ability to continuously pay, comply, and endure.

The Constitutional Cost

Indiana courts have declined to recognize a private right of action for damages under the Indiana Constitution (Cantrell v. Morris, 849 N.E.2d 488 (Ind. 2006)). As a result, individuals subjected to pretrial detention and supervision have limited state-level remedies, even when harm is substantial.

The system internalizes efficiency and externalizes cost.

Pretrial detention drains defense resources.

Supervision fees replace preparation funds.

Choice of counsel erodes before trial begins.

The presumption of innocence survives on paper, but not in practice.

Where This Leaves the Series

Part I showed how discretionary encounters begin the process.

Part II explained why insulated decision-making is rarely corrected.

Part III demonstrates how bail, risk assessment, and pretrial supervision convert arrest into punishment before adjudication, while quietly undermining the right to a meaningful defense.

The final installment will examine how these pressures converge—how plea decisions are shaped, how cases resolve under financial and temporal coercion, and how the system trades truth-finding for throughput.

The system does not need a conviction to secure compliance.

It only needs time, leverage, and money.