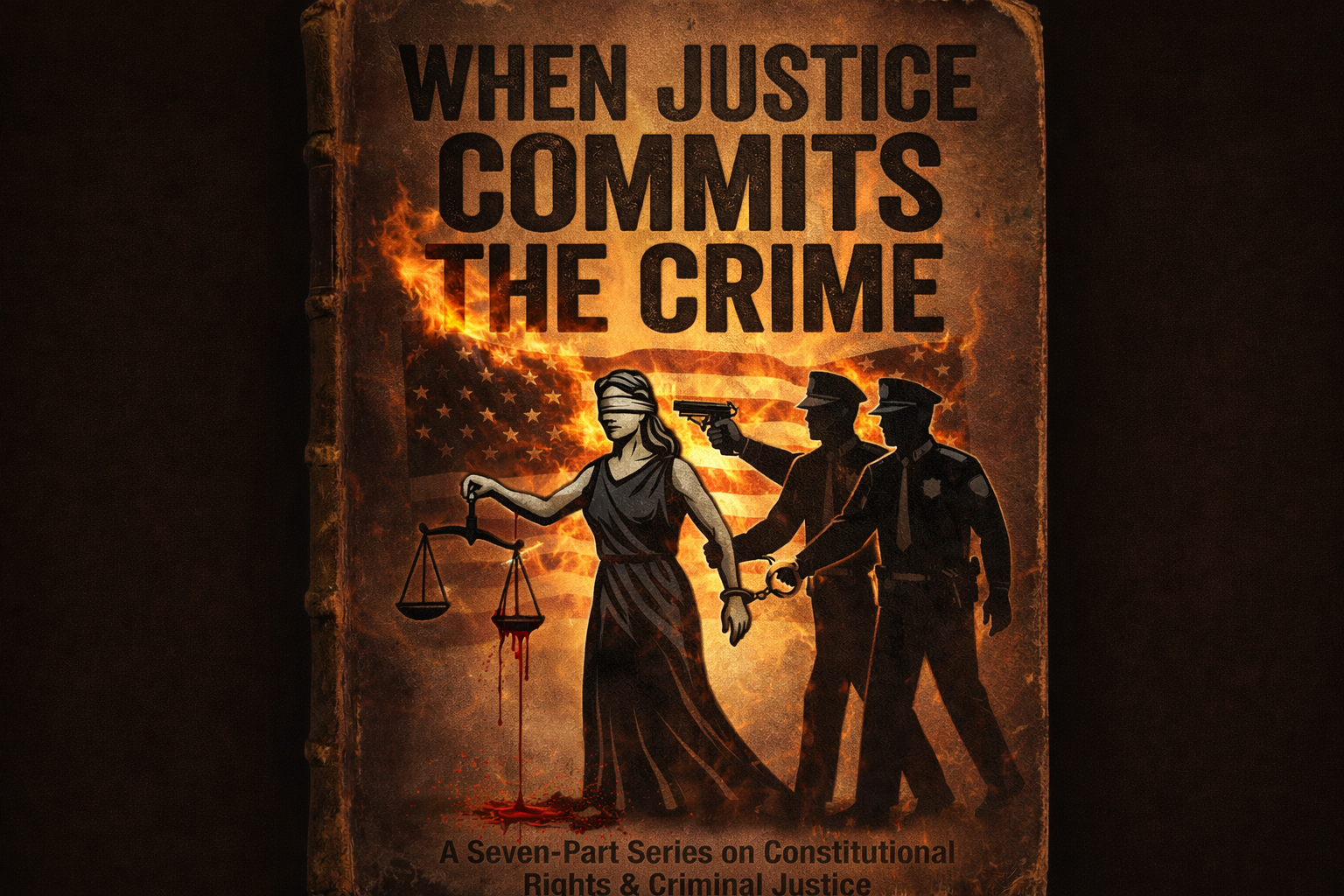

WHEN JUSTICE COMMITS CRIME: CONCLUSION

WHEN THE SYSTEM BECOMES THE CRIME

Imagine a city that installs fire alarms in every building, mandates evacuation plans, and trains firefighters—then quietly disables the water supply. When buildings burn, officials point to the alarms and say the system worked. The presence of safeguards becomes the defense for their failure.

That is how this system operates.

Indiana’s criminal justice framework is filled with constitutional alarms: the presumption of innocence, the right to counsel, the right to trial, the prohibition against excessive bail. Each exists on paper. Each sounds, briefly. But the mechanisms required to give them force—time, resources, scrutiny, accountability—are systematically drained away. What remains is procedure without protection.

This is why reform stalls. The system does not see itself as broken. From the inside, it appears efficient. Cases move. Dockets clear. Budgets stabilize. The harm is externalized onto individuals who lack standing, leverage, or longevity in the process. Like a factory dumping waste downstream, the damage occurs out of sight, borne by those least able to document it.

Courts normalize this because normalization is the only way the system remains administrable. If every pretrial detention were treated as punishment, if every coerced plea were treated as a constitutional failure, if every informant death were examined as state-created risk, the system would grind to a halt. So instead, these outcomes are reclassified as unfortunate, collateral, or inevitable. Law does not deny the harm; it reframes it.

What makes this a crime against citizens is not intent, but design. A system that predictably strips liberty before guilt, exhausts defense before adjudication, pressures resolution over truth, and outsources danger without accountability is not merely failing its obligations. It is violating the trust that justifies its authority. Citizens consent to be governed on the promise of protection, not attrition.

Accountability, if it were taken seriously, would not look like another commission or training module. It would look disruptive. It would mean counting the true cost of pretrial detention, litigating suppression as a norm rather than an exception, funding defense at parity with prosecution, and treating informant use as state action carrying state responsibility. It would mean accepting fewer convictions in exchange for legitimate ones.

Until then, the system will continue to do what it does best: point to its rules while breaking its promises. And like that city with silent hydrants, it will insist it is not responsible for the fires—only for responding to them after the damage is done.

Editor’s Note

This series was not written to persuade, inflame, or advocate for a particular outcome. It was written to document a system as it currently operates.

Every stage examined—from policing encounters to qualified immunity, bail practices, pretrial detention, defense depletion, institutional incentives, and the use of informants—relies on publicly observable processes, statutory frameworks, court decisions, and documented outcomes. Where individual cases are referenced, they are cited not as anecdotes, but as examples of how policy and practice intersect in real lives.

The conclusions drawn here do not depend on alleged intent or individual misconduct. They follow from structure. A system can violate its obligations without malice, and harm can occur without any single actor stepping outside the rules. When outcomes are predictable, repeatable, and insulated from correction, they cease to be accidents.

This project treats constitutional guarantees not as abstractions, but as operational promises. The question it asks is not whether the law says the right things, but whether the system delivers what it promises in practice. Where it does not, that gap deserves to be recorded.

Readers are encouraged to verify the sources, review the statutes, examine the cases, and reach their own conclusions. The record is open. The processes are public. What remains is whether they will be examined—or merely accepted.

— Editor, Wabash Watchdog