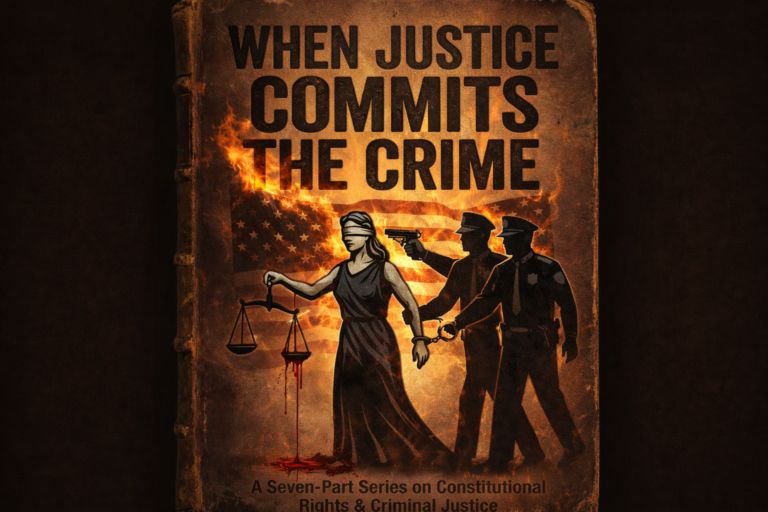

WHEN JUSTICE COMMITS CRIME: PART 6

Disposable Defendants: Informants, Risk, and the Absence of Accountability

By the time a criminal defendant is asked to cooperate as an informant, the safeguards of the adversarial system have already thinned.

They are often detained or facing detention.

They are financially exhausted.

They are represented within a system optimized for resolution, not resistance.

What follows is rarely voluntary cooperation in any meaningful sense. It is compliance extracted under pressure, with risks borne almost entirely by the accused.

The Informant as a Substitute for Investigation

Law enforcement agencies routinely rely on confidential informants to generate cases, particularly in narcotics and conspiracy investigations. Informants are used to arrange controlled buys, introduce officers to targets, wear recording devices, or provide intelligence from inside criminal networks.

In Indiana, as elsewhere, these informants are frequently criminal defendants themselves—people facing charges who are offered leniency, reduced exposure, or relief from detention in exchange for cooperation.

Unlike police officers, informants receive:

- no formal training,

- no legal education,

- no standardized safety preparation,

- and no qualified immunity.

They are sent back into dangerous environments alone.

Indiana Cases: Cooperation That Turned Fatal

The risks faced by informants are not theoretical. Indiana has seen multiple cases where cooperation with law enforcement preceded serious harm or death, with little resulting accountability.

Matthew Johnson and Christina Dixon — St. Mary’s River (Indiana)

In 2024, Matthew Johnson and Christina Dixon were found dead, their bodies recovered from the St. Mary’s River. Indiana authorities publicly identified both as confidential informants who had recently assisted police in a drug investigation.

According to reporting, the pair had led officers to a significant drug bust shortly before their deaths. They were later shot and killed, their bodies discarded. A suspect was arrested in connection with the murders, but the case raised immediate concerns about how informants are protected once their cooperation becomes known.

No criminal or civil liability attached to law enforcement for exposing the informants to retaliation. The deaths were treated as tragic but external—violence attributed to criminal actors rather than examined as a foreseeable risk of state-directed cooperation.

The informants were replaced. The system moved on.

Fort Wayne: A Hit Put on a Confidential Informant

In a separate Indiana case, court records in Fort Wayne revealed that a $10,000 hit had been put out on a confidential informant during a narcotics investigation. The informant repeatedly warned police that their identity had been exposed and that their life was in danger.

Despite those warnings, there was no indication of a formal protective framework or accountability mechanism triggered by the threat. While this case did not end in a confirmed killing, it illustrates the retaliation risk informants face once cooperation becomes known—and the absence of a system designed to respond meaningfully to that risk.

Again, the danger was treated as collateral rather than structural.

No Training, No Oversight, No Remedy

What unites these cases is not geography or offense type, but institutional design.

Informants are not trained like officers.

They are not protected like officers.

They are not insured like officers.

And when they are injured or killed, they are rarely acknowledged as acting under the direction of the state.

Courts routinely frame informant harm as voluntary risk, even when cooperation is induced by detention, charging leverage, or implicit promises of leniency. Qualified immunity shields officers. Prosecutorial discretion shields cooperation decisions. Municipal liability is difficult to establish.

The result is a system where risk is outsourced, but responsibility is retained nowhere.

Cooperation Without Consent

Consent obtained under threat of continued incarceration is not consent in any meaningful constitutional sense.

Courts recognize coercion in other contexts. See Schneckloth v. Bustamonte, 412 U.S. 218 (1973). Yet informant agreements—often informal, undocumented, or vaguely defined—are rarely subjected to comparable scrutiny.

Defendants are asked to place themselves in danger:

- without formal training,

- without enforceable safety guarantees,

- without meaningful judicial oversight,

- and often without full consultation with counsel.

What is described as cooperation is frequently survival behavior.

Why Accountability Never Arrives

When informants are harmed, several doctrines converge to prevent review:

- Qualified immunity shields officers from civil liability.

- Prosecutorial immunity shields charging and cooperation decisions.

- Lack of documentation obscures promises made.

- Plea agreements foreclose appellate review.

- Public framing casts informants as criminals who “knew the risk.”

The informant is not treated as a citizen acting at the state’s direction, but as a disposable intermediary.

This framing ensures the practice continues without consequence.

The Cost the System Never Counts

The informant pipeline produces arrests and convictions. It also produces:

- dead informants,

- traumatized families,

- retaliatory violence,

- and evidence tainted by inducement and fear.

These costs do not appear in budgets, performance metrics, or conviction statistics. They are absorbed privately, quietly, and permanently.

The End of the Line

Part I showed where power enters the system.

Part II showed why it is insulated.

Part III showed how bail and risk punish before guilt.

Part IV showed how defense is weakened.

Part V showed how institutional alignment favors speed over scrutiny.

Part VI shows what happens when all of that pressure is turned outward—onto the accused themselves, repurposed as tools.

The system does not protect informants because it does not need to.

It replaces them.