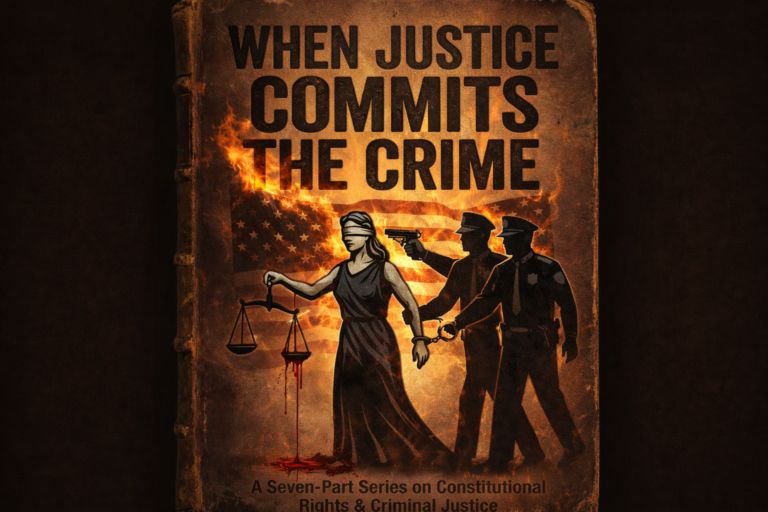

WHEN JUSTICE COMMITS CRIME: PART 5

Aligned Incentives and Unequal Arms

The criminal justice system is premised on adversarial balance. The state prosecutes. The defense resists. The court referees. A jury decides.

That balance collapses when one side of the adversary arrives with an institution behind it—and the other arrives alone.

One Paymaster, Unequal Power

In Indiana, both prosecutors and public defenders are publicly funded. Prosecuting attorneys are funded under Indiana Code § 33-39, while public defense operates through county appropriations and partial state reimbursement under Indiana Code § 33-40-7, administered by the Indiana Public Defender Commission.

This arrangement is constitutionally permissible. Public funding alone does not violate the Sixth Amendment. See Polk County v. Dodson, 454 U.S. 312 (1981).

But constitutional permissibility is not the same as functional parity.

The problem is not that both sides are paid by the same public entity. The problem is that only one side receives the benefit of the state’s entire enforcement apparatus.

The Prosecutor Never Works Alone

A prosecutor does not investigate cases personally. The office operates with the full weight of the state behind it:

- Police departments conduct investigations

- Officers generate reports and testimony

- Detectives perform follow-up work

- Crime labs handle forensic analysis

- Prosecutor-assigned investigators assist case development

- Victim advocates and administrative staff support case flow

These resources exist regardless of how many cases the prosecutor files. They are not billed to the prosecutor’s office in the way defense investigation is billed against limited defense funds.

As a result, the prosecution’s workload is distributed across agencies. The system absorbs the labor.

The prosecutor rarely becomes overloaded because the system works for them.

The Defense Works Alone

Public defenders do not enjoy that infrastructure.

When a defender needs investigation, they must request funding, locate investigators, justify expenses to the court, and often perform investigative labor themselves when funds are denied or delayed.

They do not control evidence collection.

They do not direct forensic testing.

They do not have officers gathering facts on their behalf.

They respond to a record already created by the state.

Every motion filed is additional work. Every hearing consumes scarce time. Every trial compounds caseload pressure.

Caseloads and the Quiet Push Toward Resolution

Public defenders in Indiana routinely carry caseloads exceeding national standards. Excessive caseloads impair effective representation, a principle recognized in United States v. Cronic, 466 U.S. 648 (1984), where the Court acknowledged that systemic conditions can render counsel ineffective without any single identifiable error.

Under these conditions, resistance becomes expensive.

A suppression motion requires time.

A contested hearing requires preparation.

A trial requires weeks of work.

A plea ends the case.

From the institution’s perspective, pleas are efficiency. From the defendant’s perspective, they are often the only survivable option.

Tippecanoe County’s Practical Reality

In Tippecanoe County, the prosecutor’s office, courts, sheriff’s department, jail, and public defense all operate within the same county budgetary ecosystem.

While funds are technically allocated to separate departments, the county bears the cumulative cost of:

- Extended detention

- Jury trials

- Expert witnesses

- Prolonged litigation

Trials are expensive. Pleas are not.

No written policy is required for this pressure to exist. It is embedded in how institutions experience cost, time, and administrative strain.

An Adversarial System in Form Only

This does not require corruption. It requires only alignment.

When one side is supported by institutional machinery and the other is constrained by scarcity, the adversarial process becomes symbolic. The contest still occurs—but the outcome is increasingly predetermined by structure rather than merit.

Plea as Survival: When Guilt Is Redefined

By the time most defendants are offered a plea, the case has already been decided in every way except on paper.

A defendant facing pretrial detention, supervision fees, lost income, and depleted savings confronts a stark equation:

- Continue resisting and remain incarcerated or financially unstable

- Or resolve the case quickly and regain limited freedom

This decision is not made in a vacuum. It is shaped by earlier stages: bail practices, defense depletion, investigative imbalance, and institutional pressure.

Plea bargaining becomes less about culpability and more about endurance.

The Vanishing Trial

Trials are no longer the centerpiece of the criminal justice system. They are statistical anomalies.

The overwhelming majority of criminal cases resolve through plea agreements. This is not because guilt is always clear, but because trial has become an irrational risk—financially, psychologically, and structurally.

The Supreme Court has acknowledged the centrality of plea bargaining to modern criminal justice. See Missouri v. Frye, 566 U.S. 134 (2012); Lafler v. Cooper, 566 U.S. 156 (2012).

But acknowledgment is not endorsement.

Plea Bargaining as Risk Management

Plea negotiations often begin early—sometimes before discovery is complete, before motions are litigated, and before suppression issues are tested.

The defendant is asked to waive rights without ever seeing them exercised.

This transforms the meaning of guilt. Admission becomes a strategic decision rather than a factual one.

The system rewards speed, not scrutiny.

What Is Lost

When cases resolve through plea:

- Police conduct is rarely reviewed

- Suppression issues remain unlitigated

- Constitutional violations go unexamined

- Appellate records are never created

The law stagnates because it is never tested.

Justice becomes administrative.

Efficiency as a Moral Value

The system increasingly treats efficiency as virtue. A fast case is a good case. A resolved case is a successful case.

But efficiency is not justice.

When liberty is conditioned on agreement rather than truth, the presumption of innocence is replaced by a presumption of settlement.

By the time a plea is entered, the outcome reflects not just the facts of the case, but the accumulated pressure of every stage before it.

The system has not malfunctioned. It has performed exactly as designed.

What remains is the question of accountability—how these practices are insulated from review, normalized through repetition, and defended as necessity.

That is where the system becomes most invisible.