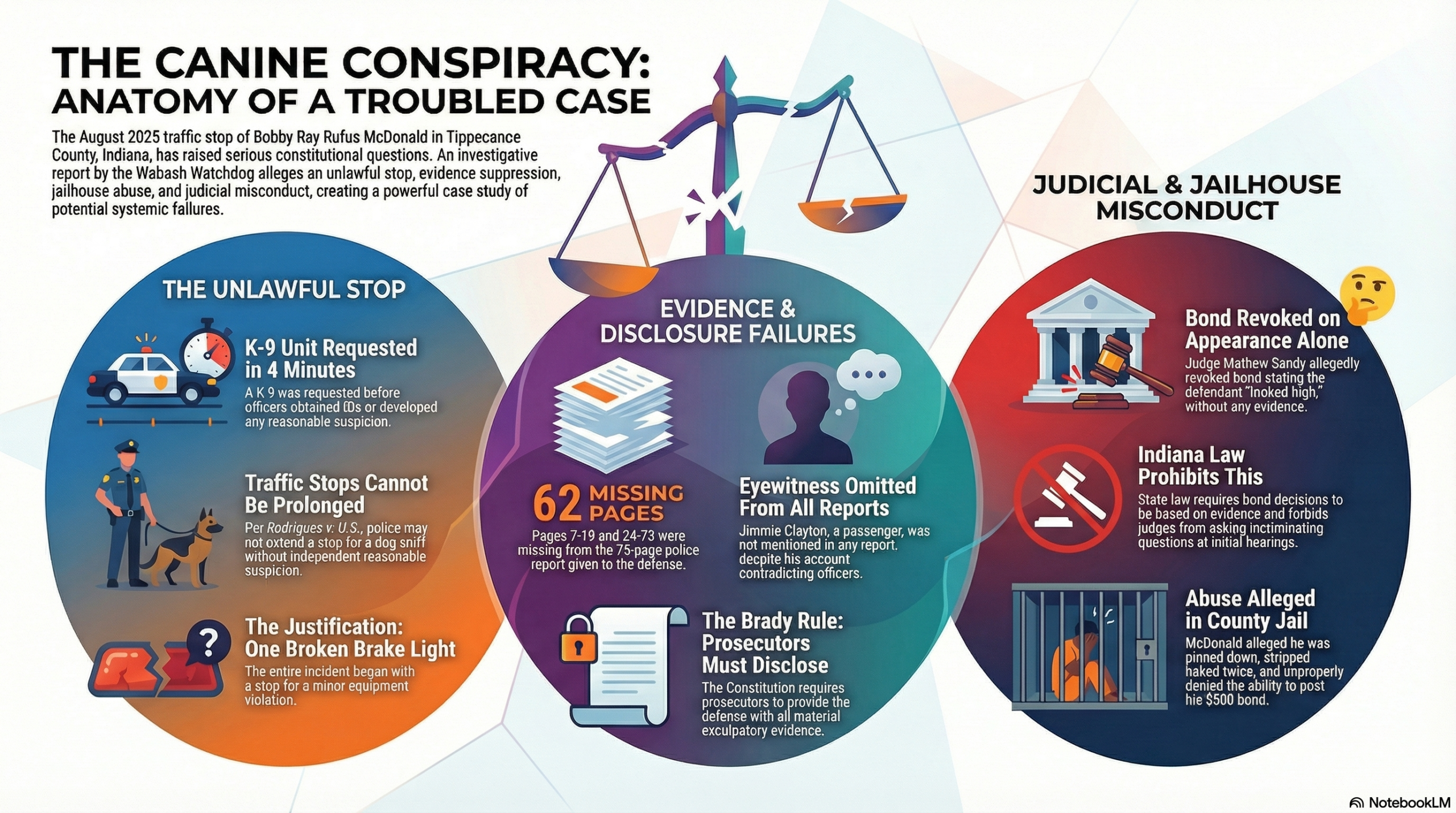

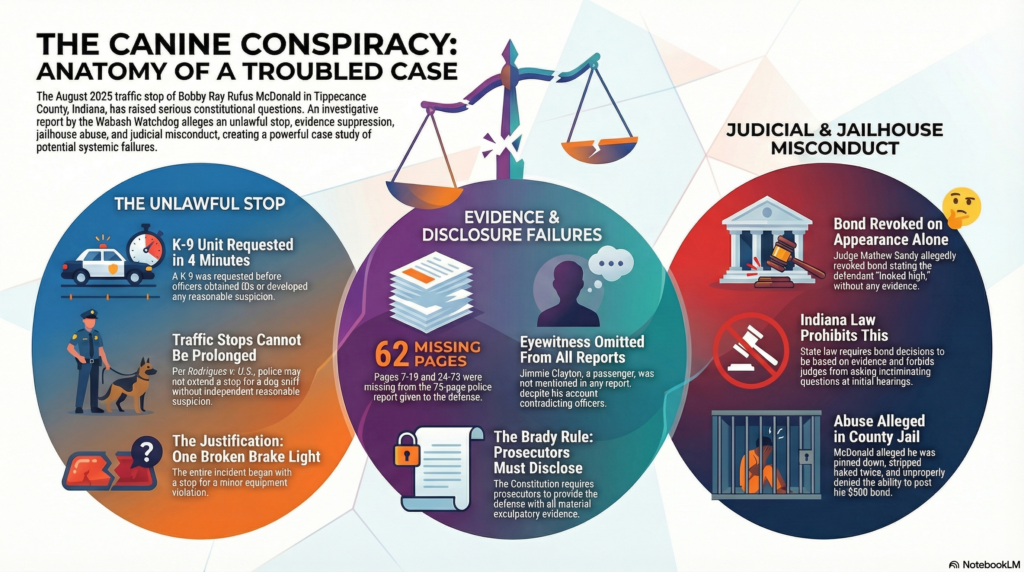

Canine Conspiracy: A 1st Account of a Constitutional Collapse in Tippecanoe County

Canine Conspiracy

By Jimmie L. Clayton, Jr., Editor-in-Chief, The Wabash Watchdog

Introduction: A View From the Passenger Seat

I was there. When the blue and red lights flooded the cabin of the truck in the early morning hours, I was not just another reporter working on another story. I was an eyewitness, sitting in the passenger seat as deputies from the Tippecanoe County Sheriff’s Office pulled over Susie Williams-Hill. I followed this case from the side of the road to the doors of the county jail and sat in the pews during the initial hearing. What I witnessed was not a simple traffic stop, nor was it a routine application of the law. It was a calculated and unconstitutional trampling of fundamental rights, and I have come to call it the “Canine Conspiracy.”

Let me be unequivocal: this single case does not reveal a failure of the system. It reveals the system functioning as a machine of injustice, and I saw every gear turn. From the pretextual roadside stop orchestrated by sheriff’s deputies, to the deliberate concealment of evidence by investigators, to the punitive and abusive conditions within the county jail, and culminating in a shocking display of judicial bias from the bench, the system did not just bend the law—it broke it, repeatedly and with impunity.

This editorial will walk you, the reader, through each stage of this constitutional collapse. By juxtaposing my firsthand, eyewitness account with the official police reports and court records, I will expose a system that appears to be operating not in service of the law, but in open defiance of it.

1. The Stop: A Pretext in Plain Sight

The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is not a suggestion; it is a command. During a routine traffic stop, police authority is strictly limited to the mission of that stop—addressing the traffic violation. In its landmark ruling in Rodriguez v. United States, the Supreme Court made it unequivocally clear: police may not prolong a traffic stop beyond the time reasonably required to complete its original mission just to conduct a K-9 sniff, unless they have developed independent, reasonable suspicion of criminal activity. This rule exists for a clear reason: to prevent law enforcement from turning every minor speeding ticket or broken taillight into a speculative, warrantless drug search, thereby protecting citizens from arbitrary extensions of state power.

On the night of the incident, the mission of the stop was a minor traffic infraction. Yet, the actions of the deputies on the scene revealed a different agenda entirely. From my vantage point, the sequence of events was a clear violation of the principles laid out in Rodriguez. The deputies initiated the stop, and before they had even secured identification from the vehicle’s occupants or had any meaningful interaction that could have possibly given rise to “reasonable suspicion,” they were already setting the stage for a drug search.

The Computer-Aided Dispatch (CAD) log, an objective, time-stamped record of police communications, confirms this unconstitutional overreach. Between 2:17:35 a.m. and 2:18:52 a.m., Deputy Peterson transmitted the message: “REQUESTING K9.” This request was made before officers had obtained our IDs, before they had observed any of the supposed “suspicious behavior” they would later invent for their reports, and while they were still in the process of conducting the initial tasks of the traffic stop. This was a classic case of unlawfully prolonging a stop, a direct contravention of Rodriguez. The official narrative constructed afterward only deepens the deception.

THE OFFICIAL NARRATIVE

THE TRUTH THAT I WITNESSED

Deputy Sapp claimed he observed McDonald “moving leaves and sticks around him” in the grass, implying he was concealing something.

Deputies ordered McDonald to exit the vehicle and sit in the public grassy area beside the road. He only picked up his phone from the ground after being accused of hiding something.

Drugs were “discovered” in the public grassy area near where McDonald had been sitting, forming the basis for the arrest.

The K-9 unit arrived but never alerted to the presence of narcotics. I kept a keen eye on the K9 and it’s handler for a story idea that I’ve been brainstorming. It deals with audio and gesture commands. No contraband of any kind was found on McDonald’s person or inside the vehicle.

This initial encounter was not a legitimate law enforcement action; it was an unconstitutional pretext from the start. Having manufactured probable cause out of thin air, the deputies now faced a new challenge: ensuring their fiction would survive the scrutiny of the record. This required a second, more insidious act—not of commission, but of deliberate omission.

2. The Investigation: A Conspiracy of Omission and Deceit

The duty of a prosecutor—and by extension, the police who investigate on their behalf—is not merely to win cases, but to see that justice is done. Central to this duty is the constitutional mandate established in Brady v. Maryland, which requires the state to disclose any evidence that is favorable to the accused, known as exculpatory evidence. A failure to do so, a “Brady violation,” undermines the very foundation of a fair trial by preventing the defense from challenging the state’s case with all available facts.

In the case of Bobby McDonald, the investigation was poisoned by one of the most flagrant violations I have ever witnessed. I, Jimmie Clayton, was a direct eyewitness to the entire traffic stop. I provided my identification to a Lafayette Police Department officer who arrived on the scene. My testimony directly contradicts the official narrative regarding the K-9’s non-alert and the sequence of events on the roadside. And yet, I was omitted entirely from all police reports. This was not a mere oversight. It was a textbook example of an officer omitting facts that “any reasonable person would have known the judge would wish to have brought to his attention.” This deliberate act of concealing exculpatory evidence is not just a Brady violation; it demonstrates a “reckless disregard for the truth” under the standard set in Franks v. Delaware, poisoning the probable cause affidavit from its inception.

This conspiracy of omission extends to the official discovery documents. The incident report is listed as 75 pages long, but vast sections of it are simply gone. The Incident Report is missing:

• Pages 7 through 19

• Pages 24 through 73

These are not minor gaps. They conceal crucial narrative details, photo logs, and internal communications. Withholding this information makes a proper defense virtually impossible and constitutes a flagrant defiance of Indiana’s brand-new Rules of Criminal Procedure, Rule 2.5. This rule on automatic discovery, part of a major overhaul effective January 1, 2024, was specifically designed to promote transparency. To shred the official report in this manner is not just non-compliance; it is an audacious rejection of reform.

This pattern of deception violates the bedrock legal principle that demands a “truthful showing” in affidavits used to establish probable cause. The Indiana Supreme Court, in Heuring v. State, affirmed that when affidavits are “so lacking in probable cause,” the good-faith exception to the exclusionary rule does not apply. When law enforcement fabricates a narrative, deliberately omits a key exculpatory witness, and withholds the majority of the official report, their actions are not a reasonable mistake. They are objectively unreasonable. When the official record is a work of fiction, it is no surprise that the treatment of the accused behind closed doors becomes a testament to unchecked power.

3. The Jail: Punishment Before Process

The Tippecanoe County Jail is not an isolated facility with a few bad actors; it is an institution with a long and documented history of constitutional failures. Federal court records reveal a pattern of civil rights litigation against both past and present sheriffs. The class-action lawsuit in Olson v. Brown, which alleged a systemic denial of inmates’ access to the courts by ignoring grievances and improperly handling legal mail, established the very culture of impunity that enables abuse. That culture’s predictable consequences are seen in Bartole v. Goldsmith, a more recent case against the current sheriff alleging retaliation and inhumane conditions. Bobby McDonald’s case is not just another data point; it is the direct and foreseeable outcome of these documented, unaddressed institutional failures.

His allegations about his treatment inside the jail, if proven, are not just instances of poor treatment but potential violations of federal law.

• Excessive Force and Punitive Conditions (Fourteenth Amendment Violations):

◦ He alleges he was taken to the ground by multiple officers.

◦ He was pinned while stating, “I can’t breathe.”

◦ He claims he was stripped naked on two separate occasions.

◦ He was kept in a cell without bedding or even a mattress.

• Denial of Pretrial Liberty (Eighth Amendment & Due Process Violations):

◦ He was denied the ability to post bond, despite having the $500 cash bond available.

◦ He was only permitted to post bond the following day, after an officer he personally knew happened to see him and intervened on his behalf.

These are not trivial complaints. The alleged use of excessive force against a pretrial detainee points directly to a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. The arbitrary denial of his right to post a legally set bond is a breach of the Eighth Amendment and the Due Process Clause. Together, these actions form the basis of a 42 U.S.C. §1983 federal civil rights lawsuit—the very same legal tool used in prior lawsuits against the jail’s leadership. When viewed against this backdrop, McDonald’s experience suggests that punishment before process is not an anomaly at the Tippecanoe County Jail; it is the norm.

4. The Hearing: A Courtroom Devoid of Law

The final safeguard for a citizen accused of a crime should be the courtroom, where a neutral magistrate ensures that the law is followed. Under Indiana Code § 35-33-7-5, the purpose of an initial hearing is strictly defined: a judge is to advise a defendant of the charges and their rights. The law exists to protect the presumption of innocence and the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination, ensuring the hearing remains a procedural checkpoint, not a premature trial. At the November 14th initial hearing for Bobby McDonald, however, Judge Mathew Sandy transformed this safeguard into the final point of constitutional collapse.

The hearing began as expected. McDonald was informed of the charges and requested a public defender. At this point, the law required Judge Sandy to move on to the neutral matters of his bond and counsel. Instead, he initiated a line of questioning that was both improper and illegal. He asked McDonald: “Could you pass a urine screen today?”

This question is an interrogation designed to elicit an admission of drug use—a fact directly related to guilt. It is a blatant violation of the statute. When McDonald answered honestly that he wasn’t sure and was trying to get into treatment, Judge Sandy abandoned any pretense of judicial impartiality, responding with a bullying and contemptuous diatribe: “If you wanted in rehab, you’d be in rehab. If you wanted to quit smoking meth, you’d quit smoking meth.”

The hearing culminated in Judge Sandy revoking McDonald’s bond. The legal basis was not evidence, testimony, or a risk assessment. The judge’s sole justification, stated in open court, was his personal observation that McDonald “looked high.” This action flagrantly violates multiple Indiana laws and rules designed to prevent such arbitrary deprivations of liberty. It shocked my conscience to the core.

• Indiana Code § 35-33-7-6: This law requires that bond decisions be based on evidence of risk of flight or danger to the community. A person’s physical appearance is not evidence.

• Ind. Criminal Rule 2.6: This modern reform mandates the use of validated, evidence-based risk assessments to guide pretrial release decisions, replacing a judge’s subjective “gut feeling” with objective criteria. No such assessment was performed.

• Judicial Canons: The bedrock principles of our legal system require judges to be impartial and to prohibit bias from influencing their decisions. Judge Sandy’s conduct and comments displayed a clear personal bias that has no place on the bench.

In that courtroom, due process died. The initial hearing, which should have been a shield protecting a defendant’s rights, was instead wielded as a sword, where a judge unilaterally abandoned statute, evidence, and impartiality in favor of his own gut feeling. Honestly, I don’t know why the Deputy Prosecutor came to the hearing, because Judge Sandy was doing a terrific job at the role of Prosecuting Attorney.

Conclusion: A System on Trial

What I witnessed firsthand in the case of Bobby McDonald was not an isolated incident or a series of unfortunate errors. It was the complete and systematic breakdown of constitutional protections at every critical junction of the justice system in Tippecanoe County. It began with an illegally prolonged traffic stop and the falsification of official reports to manufacture probable cause. It continued with a conspiracy of omission to conceal exculpatory evidence from the defense. It manifested in the county jail through punitive treatment that amounted to punishment before trial. And it was cemented in a courtroom where a judge disregarded Indiana law and the presumption of innocence in favor of personal prejudice.

The “Canine Conspiracy” is more than one man’s journey through a broken system. It is a chilling indictment of a system where the actions of law enforcement, correctional staff, and even the judiciary appear dangerously unchecked.

We do not call for vague promises of reform. We demand a public accounting from Sheriff Goldsmith, a review of every case prosecuted on the word of these deputies, and an investigation by the Indiana Commission on Judicial Qualifications into the conduct of Judge Sandy, which was initiated. The system is on trial, and the Wabash Watchdog will be in the front row, taking notes.